Written by Lauren Colonair.

The Outer Banks Field Site (OBXFS) offers an abundance of opportunities for undergraduate students from UNC-Chapel Hill, however, the capstone component is one of the main attractions. Most of the students that participate in the field site are environmental science and studies majors, degrees which include a capstone research project as a requirement for graduation. There are many different ways a student can complete this requirement, but OBXFS is one of the few paths that offer the opportunity to participate in hands-on research.

For three years, the instructors of the field site Drs. Lindsay Dubbs, Linda D’Anna, and Andy Keeler have been guiding students through a study examining the interactions between septic systems and groundwater in Nags Head, North Carolina. Currently, we, the 2020 OBXFS students, are nearing the end of the final installation of this study.

We began our research by reviewing the questions, methods, and findings of the 2018 and 2019 portions of the three-year project, and from there formed research questions of our own. At the beginning of the semester, we worked with Dr. D’Anna to create our research questions for the Human Dimensions portion of the project. What are the levels of awareness, risk perception, and practices regarding septic tank systems and groundwater contamination from wastewater among property owners in Nags Head, NC?

In the past, students had collected data for this portion of the capstone through interviews. Dr. D’Anna wanted us to build off of their findings and create a survey in order to find the answers we were seeking. The result of this request was two grueling weeks of creating questions, then deciding we did not need those questions and starting all over again. By the end of the process, however, we had a product we were all proud of.

Dr. D’Anna then introduced us to the world of consent and recruitment as we begin to work on materials meant to protect our respondents’ privacy, as well as encourage people to take our survey. It was a huge learning curve working through the intensive process of creating and sending off a research survey; however, it gave us the all-important experience we would not have gained elsewhere.

We have now sent out 1,780 postcards to encourage Nags Head homeowners to fill out our survey. Responses have started to flow in and a group of us have begun analyzing the results contained with each completed survey.

“I’m really happy to see the responses coming in. These residents didn’t have to take the time out of their day to take our survey and it’s nice to see that they cared enough about this issue to respond,” said Natalie Ollis, a junior at the field site, double majoring in Biology and Environmental Studies with a minor in Business.

The second portion of our project, led by Dr. Dubbs is centered around the scientific analysis of groundwater quality in our study area. More specifically we were tasked with determining the levels of E. coli; total coliforms, a group of bacteria which live in soil, water, and the intestines of animals; and optical brighteners, a chemical found in laundry detergent, within the groundwater in Nags Head. Using this data, we are attempting to illustrate the trends and potential issues derived from septic water contaminating groundwater.

The first step in the process was collecting our samples from eleven locations, some groundwater wells and others ditches, around the study area. Dr. Dubbs prepared methods for us to follow based on the success and failures of the previous research teams. Over the course of four days spread over two months, we collected samples and environmental data from each site.

After the samples were collected, we would take them to the lab to analyze the water. The lab work required us to learn new skills quickly, as the work for this research is very different from lab work for a biology or chemistry class. Under the guidance of Dr. Dubbs though, the steps of analysis become second nature.

To process our E. coli and complete coliform samples, replicates were prepared and sealed into a tray, which was then incubated for 24 hours. Replicates are smaller, identical samples created from the water collected at each site. By using replicates we were able to average the results of each and increase the precision of our measurements. Within the tray, the bacteria would begin to grow, and when they were examined the next day we were able to determine the levels of each bacteria within the sample. Complete coliforms were indicated by cells in the tray which had turned yellow, and E.coli was indicated by cells in the tray which glowed under UV light.

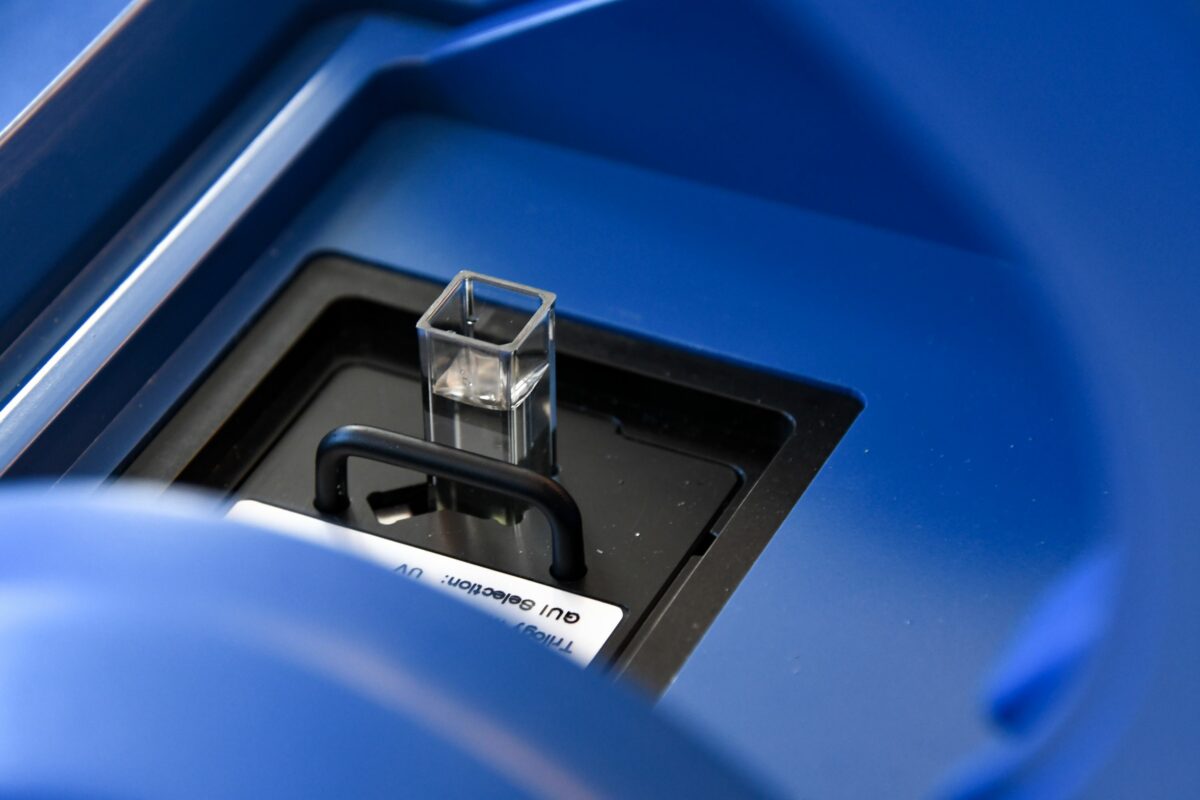

Our optical brightener samples were processed on the same day they were collected. Replicates were created for each test site and analyzed using a Fluorometer, which measures relative fluorescence units, or RFU. In conjunction with a calibration curve, we used these results to determine the level of brighteners present at each sample site.

Currently, we are in the process of analyzing the data collected from each site by organizing and refining it. It can be difficult to look at such large quantities of numbers on a screen and try to understand what they mean, but we are making progress and have already begun to clarify the message our results are sending us.

Emma Bancroft, a junior at the field site who is majoring in Environmental Science said, “This process has been a challenge, but it is nice to see the project start to come together into a final product.”

Of course, the most important part of the capstone is the research paper, an element we have been working on since the start of the semester, although we only recently finalized the title- What lies beneath: A socio-ecological case study of septic systems in Nags Head.

In August, all of us worked together on a literature review in order to explain the ecological processes and ecosystems within which we were working. Since then, we have broken up into groups to draft the introduction and methods sections of our paper. As we continue to analyze our data we will begin to compose the results and discussion sections. Despite how impossible it seems now, we will have our results and a completed research paper by the end of November.

“The paper writing has been an interesting experience because it is an often overlooked form of group work,” Bri Thompson, a junior at the field site double majoring in Environmental Studies and Public Policy said, “when you are working on something that long, with different writing, explanation, and organization styles, you get good experience for how the world works. Things are not always going to go your way and you have to be open to compromise.”

Another important part of our research process is the Community Advisory Board. The CAB includes members of the local community that have volunteered their time to review our materials, progress, and results. The community-based insight we have received from the members of the CAB has been vitally important to the entire research project.

“The CAB was a great addition to the project because they gave us an insight into the community and taught us how to interact with stakeholders,” said Meagan Gates, a junior at the field site double majoring in Environmental Science and Economics.

For more reasons than one, this semester has been full of twists and turns,and the capstone is no exception. There have been really good days, where everything went right and all of us left CSI knowing we were on the right track. However, there have also been bad days, when survey questions couldn’t be agreed upon or lab analysis simply didn’t go as planned. That, though, is just the process of research, and going through the good and the bad has taught us more about research than we could have learned in any lecture hall.

Thompson spoke about the process of working as a team on a project of this scale, “you have to hold each other accountable for knowing the information. Not everyone is working on each section, but we all expect each other to stay up to date on what is going on and what we have found as we complete the project.”

Already, looking back at what we have accomplished and learned is incredible. Still more incredible is the thought that less than a month from now, thanks to our wonderful instructors and our commitment to work as a team, we will have a completed capstone research project.

Last but not least, we invite all members of the public to learn more about the Capstone and our findings by tuning in to our final presentation on Monday, November 23 at 2 PM. Following the presentation, we will be available to answer any questions posed via a chat box made available during the event. The program will be live-streamed from the CSI Youtube Channel, and a recording will also be made available.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.