Another Fall semester came and went, and with that another cohort of students from UNC- Chapel Hill wrapped up an exciting semester of courses, internships, and research.

In the last quarter of 2024, twelve students from Chapel Hill and beyond traveled to the coast to participate in the UNC Institute for the Environment’s Outer Banks Field Site hosted at the Coastal Studies Institute. Their time on the Outer Banks allowed them to focus on their education through intensive learning as well as community involvement, which somehow defied the limits of work-life balance.

Life at the Field Site

The students took classes like Coastal Law & Policy and Coastal Management; explored well-known sites such as Nags Head Woods and Jockey’s Ridge; went “down South” to Hatteras, Ocracoke, and even Portsmouth; participated in labs and workshops; interned for various environment-related organizations including the NC Coastal Reserve and NC Coastal Federation; and lived like locals, enjoying the small town shops and Thursday night line dancing at the Tiki Hut in Wanchese. As if all of that weren’t enough, they also somehow managed to complete an entire Capstone research project which they showcased at CSI’s December 2024 Science on the Sound.

At the beginning of the semester, the students completed a few “research intensives”, focusing on their Capstone and staying at the Pine Island Lodge on the Donal. C. O’Brien Sanctuary and Audubon Center property in Corolla for days at a time to better understand the Currituck Sound ecosystem and the perceptions of those who utilize it. The students recognized that the brackish marshes in the Sound are unique and face problems in the wake of climate change, erosion, and development.

The students did some birdwatching while visiting Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge.

Social Dimensions of Currituck Sound

The Capstone project was comprised of two main parts. The students addressed both social and ecological components in their study. To better understand human dimensions in the area, they conducted twelve interviews with local stakeholders to learn about the varying attitudes, perceptions, uses, and management strategies- particularly prescribed fire- of the Currituck Sound and its marshes. The interviewees included fishers, hunters, boaters, property owners, recreational users, and lifelong residents; and they were identified as interview targets for their expected knowledge of the Sound.

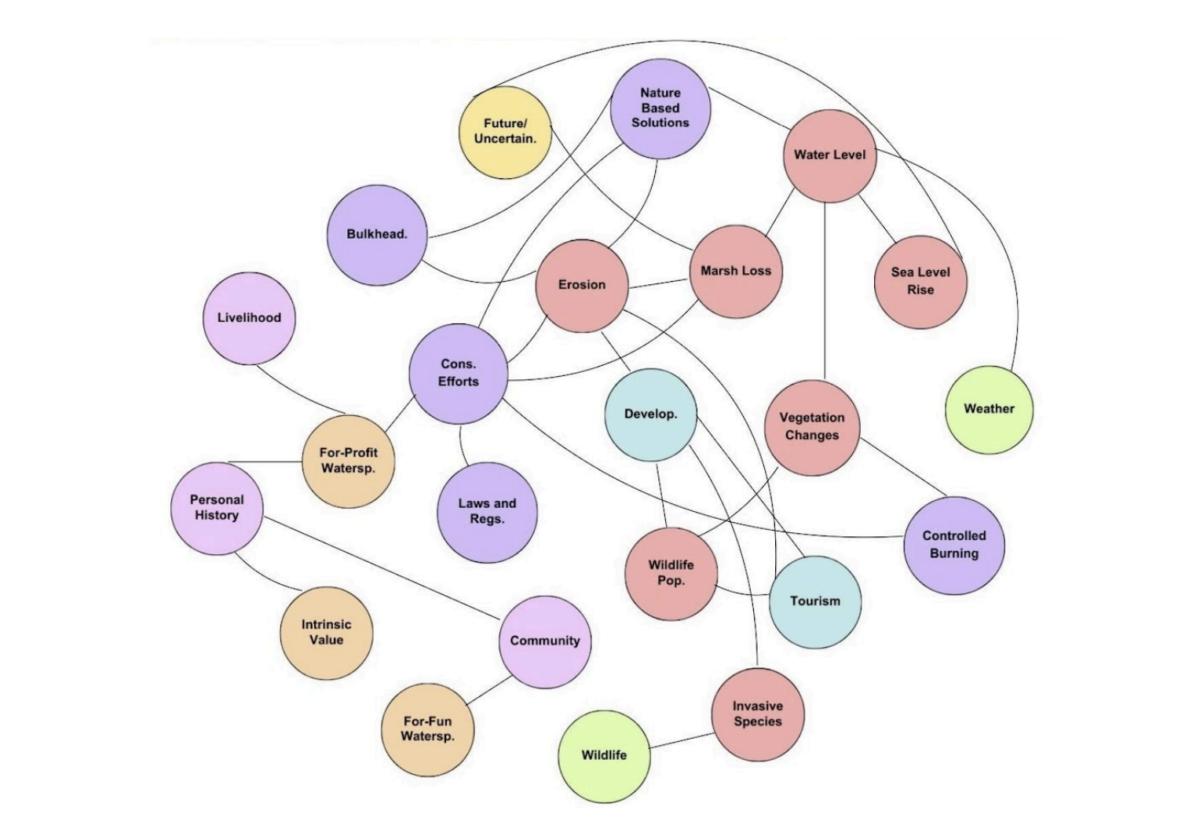

Each of the twelve students conducted one stakeholder interview. Their questions covered topics such as the individual’s history with and use of the Sound, the perceived drivers of change in the area, and observations about local management and conservation efforts like controlled burning. The students coded the interviews, a process of assigning descriptive labels, or codes, to transcript segments to organize interview data. They identified six general categories among all of the codes: Uses, Ecological Changes/ Threats, Management, Connection/ History, Human Dimension Changes, and Natural Environment. From the codes and the detailed information of each interview, the students created “mental models” to represent how each interviewee thought about Currituck Sound and used them to understand the nuanced connections among codes, as well as common attitudes and differences amongst the stakeholders.

The models revealed that individual conceptualizations of the Sound depended on the type of user and their lived experiences, but generally they all thought of the area as a place full of aquatic and wildlife resources, a place of tourism, and finally, a place for recreation and gathering with family and friends. Interviewees had a strong sense of pride in their community and a recognized appreciation for wildlife.

The interviews and subsequent models also revealed that stakeholders, overall, seem to link the increased use of natural resources, human impacts, and population growth in the area to a decrease in ecosystem quality, particularly when it comes to marsh habitat, erosion, and water quality. Stakeholders also connected the management strategy of controlled burning to ecological changes in the marsh such as healthier vegetation, thus benefiting overall habitat quality and increasing usability by users.

An example of a mental model as it appears in the students’ final Capstone Report. The model was produced using the transcript of an interview with a recreational user of the Currituck Sound. Codes are color-based on their parent codes. (Credit: The Sound of Change: Responses to Controlled Burning and Other Changes in the Currituck Sound. Figure 18. Page 57.)

The Ecological Aspect

In addition to gathering informative, qualitative data from Currituck Sound stakeholders through the interview and mental modeling process, the students also gathered quantitative data about the marshes through a variety of field sampling methods at six different sites in the Currituck Sound. The sites were picked based on accessibility and historical burn records. Two sites served as their control, having never been burned at all. Two other sites were only burned occasionally and not in the last few years, and the remaining two sites had been burned multiple years in a row.

At each of the six sites, the students examined three 1-meter-by-1meter plots to determine vegetative species variety and richness. At each plot they also took vegetation and soil samples to estimate biomass both above and below ground and soil properties. Water samples were also collected where possible.

After sifting through their ecological data, the students noticed the following trends:

- Species richness was low and varied little among sites. Common species observed across sites included black needle rush (Juncus romerianus), goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), three square (Schoenoplectus pungens), penny wort (Hydrocotyle umbellata), and cordgrass (Spartina cynosuroides).

- All sites had relatively high C-values- a numerical measure indicating how tolerant plant species may be to human disturbances- meaning each site had high quality marsh habitat. The occasionally burned sites had the highest average C-value and best supported sensitive plant species.

- The occasionally burned and frequently burned sites maintained ecological quality comparable to the untouched control sites.

- Vegetation exhibited a higher tolerance for salinity at sites that were occasionally burned compared to those that were frequently burned or not burned at all. The students suggested that the balance of disturbance and recovery at occasionally burned sites could promote more salt-tolerant species.

- Occasionally burned sites displayed the highest average aboveground biomass, and belowground biomass was notably highest at frequently burned sites. Total biomass was also highest at frequently burned sites. These findings indicate stronger root systems at the frequently burned sites, which is an important natural characteristic for capturing carbon and combating erosion.

- High levels of phosphate were measured in the surface water and pore water (contained within soil cores) at the occasionally burned sites. Ammonia levels were also high in the surface water near occasionally burned sites.

Bringing It All Together

Combining the above results from the natural science portion of their Capstone with the human dimension elements revealed from the twelve interviews, the students drew two main conclusions.

First, interviewee observations generally aligned with the research findings particularly when it came to water quality. Interviewees noted and/ or voiced concern over rising salinity as well as increased anthropogenic, or human-caused, pollution in the Sound. The high concentrations of ammonia and phosphate measured by the students at some sites in the Sound could have been a result of nutrient runoff from fertilizers. Additionally, the increased salinity tolerance of some plant species at the sample sites could indicate changes in salinity in the surrounding area.

Second, many of the interviewees had positive perceptions of controlled burning practices, providing anecdotal evidence that the vegetation grew back greener and thicker after burns and that there was seemingly less erosion taking place at burn sites. The students’ findings confirmed the stakeholders’ observations to an extent. Controlled burning resulted in positive impacts on the marsh including an increase in habitat quality and biomass when practiced in moderation. The benefits were best seen in instances where the marsh had time to recover between burns; thus, sites that are occasionally burned can increase short-term marsh resilience. Healthy soil and vegetation can help combat erosion and protect the overall marsh habitat.

While these conclusions are notable and the students were proud of their work, they did mention some limitations when presenting their findings to the public. Most of the interviewees fit the same demographics and held similar occupations. In future studies, the students suggest including a wider variety of stakeholders to encompass more diverse perceptions and opinions. Additionally, for the sake of getting the research experience, each student conducted one interview. Had only one person conducted interviews for all participants, some inconsistencies might have been avoided. Finally, the students also acknowledged their small number of sites which were not equally distributed across the Sound, as well as the myriad of variables- rain fall amounts, wind direction, etc.- that could have affected their water quality samples on any given day.

Moving forward, the students suggest an “adaptive management approach” for the marshes of the Currituck Sound. Depending on the desired outcome, managers may want to consider different burn frequencies for different benefits and scenarios.

“We believe it’s really important to incorporate the connections between our ecological findings, stakeholder perceptions, and local ecological knowledge in future management strategies,” said one student.

The Sound of Change

The students worked exceptionally hard to bring their Capstone research project to life over the course of one semester and were able to present all their methods and findings at the final 2024 installment of CSI’s Science on the Sound lecture series on December 13. Their presentation entitled “The Sound of Change: Responses to controlled burns and other changes in the Currituck Sound” was met with much enthusiasm by members of the public and received many praises from Pine Island Audubon Sanctuary Director Robbie Fearn.

After mulling over some of his own observations in previous years as well as the students’ findings, he said, “The work that these students have done has really set us up to dig in and figure out how best to manage these marshes in the Sound, and I’m very thankful for their work too.”

Since their final presentation, the students have all returned to their respective homes to gear up for another semester back in Chapel Hill. Their work on this topic may be complete, but for others, like Fearn, the work is just beginning. The public may view their presentation at any time on the CSI YouTube Channel, and a copy of their final report has been made publicly available online. For more about the Outer Banks Field site, please visit https://ie.unc.edu/field-education/field-sites/obxfs/ and https://outerbanks.web.unc.edu/.

The preceding story first appeared in the Spring 2025 edition of CoastLines.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.