Written and photographed by Emmy Trivette, OBXFS student and CSI photojournalism intern.

Residents of the Outer Banks are not strangers to the idea of pumping sand from offshore dredge sites onto local beaches, a process known as beach nourishment. While these high-dollar projects may help preserve the life of our beaches as we know and love them, many wonder how they may impact the lives of dune dwellers and those critters that live beneath the sand’s surface. Fortunately for those kept awake at night by such queries, members of the Marine Geochemistry and Coastal Dynamics Lab are working to provide answers.

Once the sand is moved to shore and bulldozers have rolled in to adjust the grains and beautify the beach again, then the work begins for the Marine Geochemistry and Coastal Dynamics Lab.

It’s their job to count and determine the mortality rates of the surf-zone critters and to define the changes in beach composition as part of impact surveys following beach nourishment. This year, lab members Dr. Paul Paris and Rebekah Littauer are focusing on sites in Avon and Buxton, North Carolina.

Impact surveys, such as the one Paris and Littauer are currently conducting, are always required by the state when a new nourishment project begins, and there are two major components that make up the geomorphology lab’s work.

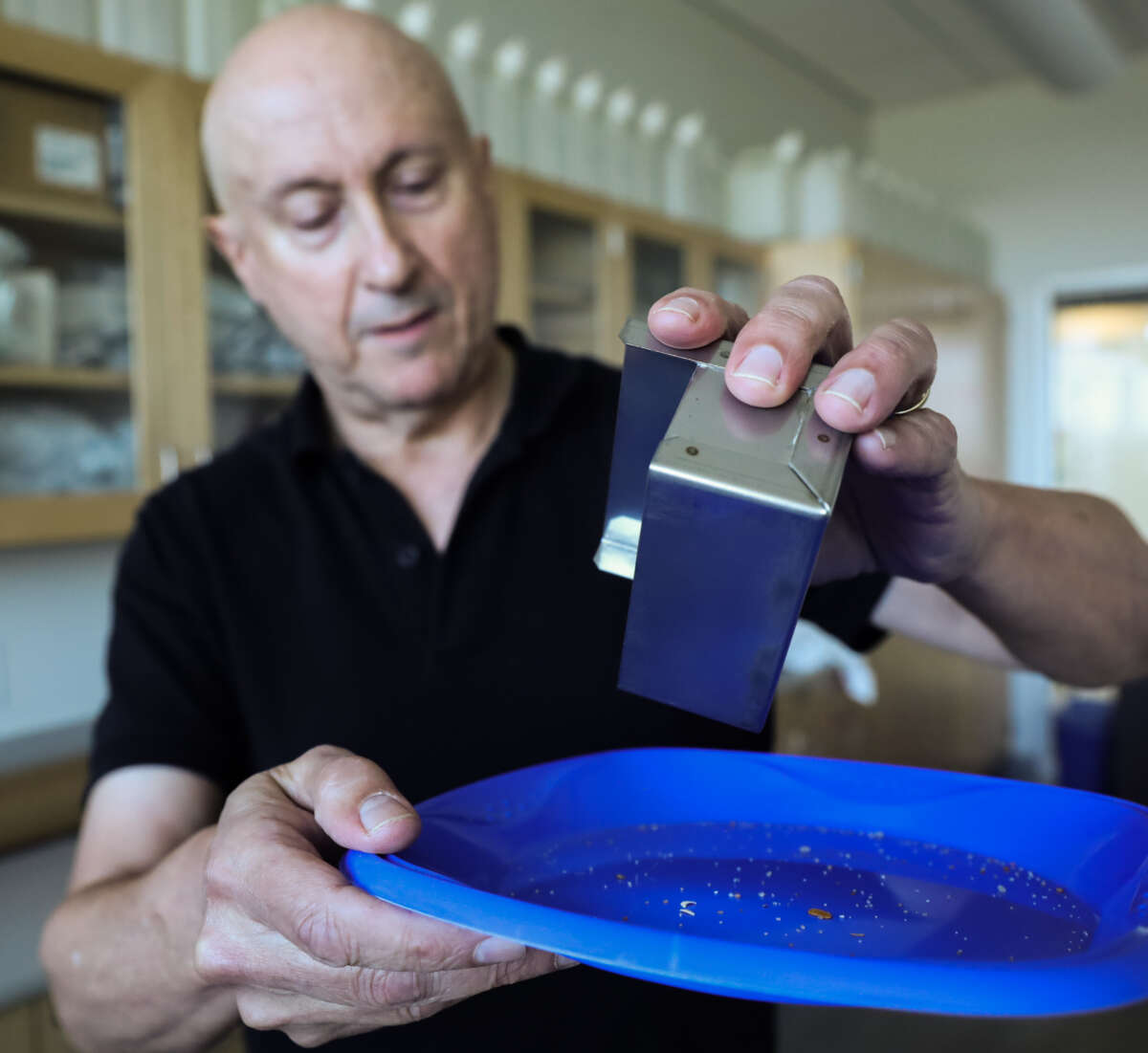

First is the heavy mineral analysis. The lab collects and takes pictures of sub-samples of sand taken from the work sites and a control site both before and after nourishment takes place. The images are then run through a software that will identify each grain sample’s density, offering a comparison of the beach composition pre- and post-nourishment.

Dr. Paul Paris processes a sample taken from one of the study sites.

“There has to be a certain degree of match, in terms of [sand grain] size distribution and mineralogical composition of the material you use to rebuild the eroded beach back,” Paris states.

The second and more tedious task includes counting invertebrates on the beach.

“The beach ecology is probably something that’s most overlooked because the motivation behind doing nourishment. 99.9% of the time, you’re trying to hold back the ocean from infrastructure situated behind the beach, including people’s homes,” says Paris.

Yet, unfortunately for the animals of the newly nourished beaches, the fresh layer of sand covers and corrodes their habitats. Paris says it’s expected for the mortality rates of the animals to be high directly after nourishment, but little until this study, little was known about the organism recovery process.

Thus, the most crucial invertebrate counts take place immediately after beach nourishment is complete. To conduct these counts, the lab team lays a plotline, stretching from the dune wrack line to the tideline, to record each crab burrow within two meters of the line. This process, otherwise known as a belt transect count, is repeated 36 times for each nourishment site.

Sand fleas, or mole crabs, are another species of interest for the study. They inhabit the “swash zone,” part of the study site where the researchers are likely to get their toes wet in the tideline. Using a sand sifter, otherwise known as a sieve, Paris and Littauer will sift three samples, record the data, and release all critters collected back to their habitats.

Lab technician Rebekah Littauer (left) lays a plotline in preparation for a belt transect count.

“It’s easy to forget [the invertebrates] are there, but the fish that fishers catch often eat these invertebrate creatures that we’re studying,” Paris explains. “If these animals disappear, the fish will go elsewhere, so it does, in the end, reflect directly into our tourist economy.”

“It really shows how so many things are intertwined. You can find all these big changes based on little things,” Littauer adds.

The out-of-sight invertebrates like ghost crabs and sand fleas make it easy for beachgoers to keep the animals out of mind when visiting their habitats, but the organisms’ presence, or their importance to the ecosystem, is not lost on the researchers. The impact surveys for Buxton and Avon will continue once every four months until the project’s end in the summer of 2024. The results of the study will create a better understanding of benthic communities and provide data to local decision-makers as they address best coastal management practices.

Photo, right or below: Littauer sifts through a sample from the swash zone looking for mole crabs.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.