All along it has seemed that Dr. Rachel Gittman’s career path has had an element of intersection. During her schooling, she studied terrestrial then marine environments. As a consultant, she often experienced the tug between scientific fact and human want. Now in academia, Gittman is a Coastal Studies Institute (CSI) Research Associate and an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biology, yet her projects often involve coastal engineering and adaptation. So how did she get to where she is today?

Gittman grew up in southern Virginia and eventually found herself studying terrestrial systems at the University of Virginia. After participating in undergraduate research opportunities and obtaining a degree in Environmental Science, she moved to Washington, D.C. for some “real world experience” and to become an environmental consultant. While holding the role for three years, Gittman had the opportunity to work with many federal clients on environmental management and compliance projects. Though the work was “interesting and versatile”, she felt that something was missing.

“I started to realize that many times compliance, management, and policy decisions weren’t really being made based on science. A lot of it was people saying, ‘Well, we think this is what is best.’ There wasn’t much scientific process associated with what I thought were important environmental management and policy decisions being made at the federal level.”, says Gittman.

She continues, “So I became interested in going to grad school because of what I perceived to be a disconnect between policy and management and then science. I had it in my mind that with a master’s degree, I could go back to consulting and really tie together science and management.”

Interestingly, other plans fell into place instead. Gittman fell in love with academia and decided to switch her focus to marine and coastal ecosystems. During her pursuit of the perfect-fit graduate program and the completion of her time as a consultant, Gittman found herself working on a living shoreline project, a shoreline stabilization method that utilizes natural and living materials instead of manmade structures such as bulkheads or jetties. Her involvement in the project led her to become interested in the cross-section of engineering and ecological restoration.

As she was accepted as a Ph.D. student at University of North Carolina’s Institute for Marine Sciences, it just so happened that coastal management and ecosystem protection was becoming a hot topic in North Carolina, and living shorelines were gaining momentum. In fact, her very first day of grad school, her advisors handed her the task of writing a proposal for a living shoreline in NC.

Through grad school and her post-doc position at Northeastern University, Gittman has continued to focus on shorelines, marshes, and coastal ecology, but has also added ecological processes and some social science aspects to the mix as well. Though she lived in Boston for a brief period, she now finds herself again in Beaufort, but this time with a joint appointment with ECU’s Integrated Coastal Programs- Coastal Studies Institute and the Department of Biology.

It is especially within the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI) that she has found herself collaborating across disciplines with other faculty members. Currently, she and her lab are working on a project that intersects engineering and ecology with Dr. Sid Narayan, Dept. of Coastal Studies Assistant Professor and CSI Assistant Scientist. Narayan is a civil and coastal engineer by training, and together the two researchers are working to assess how boat wake may be influencing a restoration site in Taylor’s Creek located in Beaufort, NC.

One of the breakwater reefs Gittman, Narayan, and their students have constructed along the coastline of the Rachel Carson Reserve.

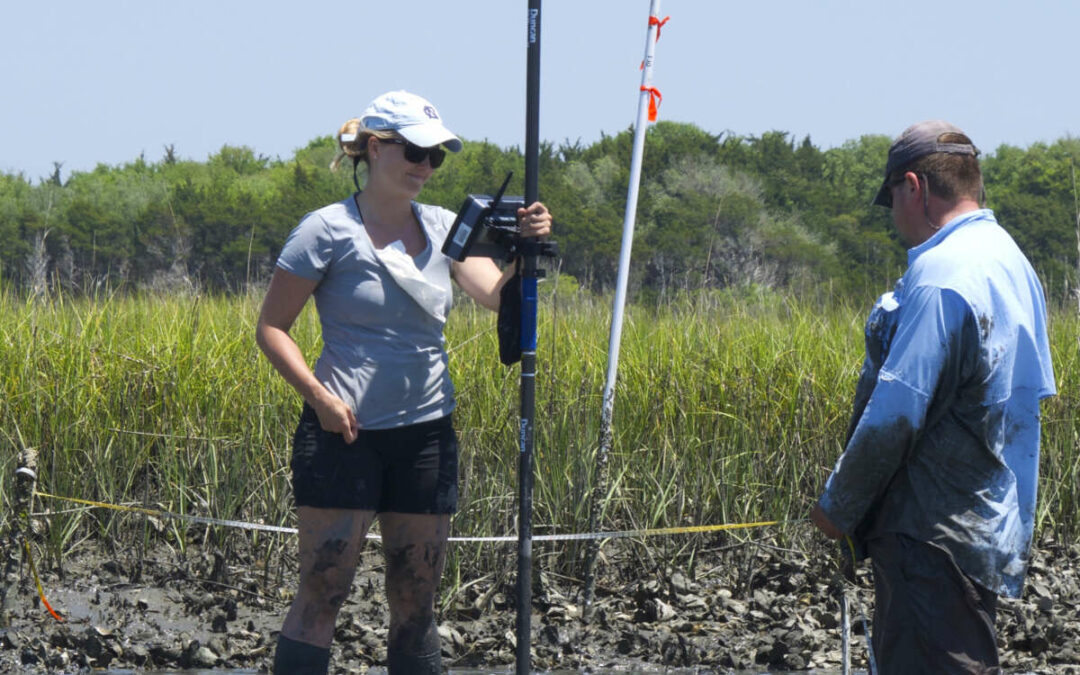

Students collect data at one of the breakwater sites.

The site lies along the Rachel Carson Reserve, which is highly subject to shoreline erosion, and is comprised of several 15 m long breakwater reefs constructed with material specially designed for oyster recruitment. Gittman, Narayan, and their grad students will monitor the site over time to assess 1) how the oyster reefs form 2) if they are comparable to a naturally occurring reef in a similar system and 3) how well the reefs provide protection for the marsh behind it. The third assessment will be determined by the amount of shoreline accretion or erosion that takes place. In addition to the ecological aspects of the study, the team hopes to quantify the wave environment in the creek setting.

“We hypothesize that the main force behind the shoreline erosion at the Reserve is boat wake,” Gittman explains. “Even though Taylor’s Creek is a no-wake zone, it’s a heavily trafficked area with a new boathouse and public boat ramp right across from our study site. Even though the boats are being driven slowly, there’s still some wake generated as they speed up, slow down, and turn around. All of the different boats in the area at a given time are mixing the waves, potentially compounding them and causing issues along the shoreline.”

The combination of expertise highlighted through this project and others Gittman has worked on has made her thankful to be a part of ECU’s Integrated Coastal Programs. Her interests clearly straddle the line between coastal ecology and engineering, which sometimes leaves her feeling like she needs “multiple Ph.D.s” to understand and combat all of the challenges. It’s because of these feelings she encourages her students not just to get good lab and field experience early on, but to also push themselves.

In closing, Gittman reflects, “Don’t be afraid to cross interdisciplinary boundaries and ask questions that require expertise out of your comfort zone. That’s what we should all be doing- trying to find the collaborations to answer the wicked, complex questions. The solution might be simple, yet it requires a lot of thought from a lot of different perspectives to get there. And in my opinion, the interdisciplinary nature of Integrated Coastal Programs is one of the most interesting characteristics of the program. It’s a real strength of ECU, and I am excited to be a part of it.”

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.