Written by Lauren Colonair.

![Local farmers are important to Dr. Rogers' research in many ways. Their close connection with the land gives them first-hand knowledge of the changes taking place in the delta. The flow of knowledge from the farmers to Rogers and vice versa is an example of how important people are in regional level science, as well as how important this science is to the people. [Photo: Dr. Kimberly Rogers]](https://www.coastalstudiesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Rogers-2-e1601058670129.jpeg)

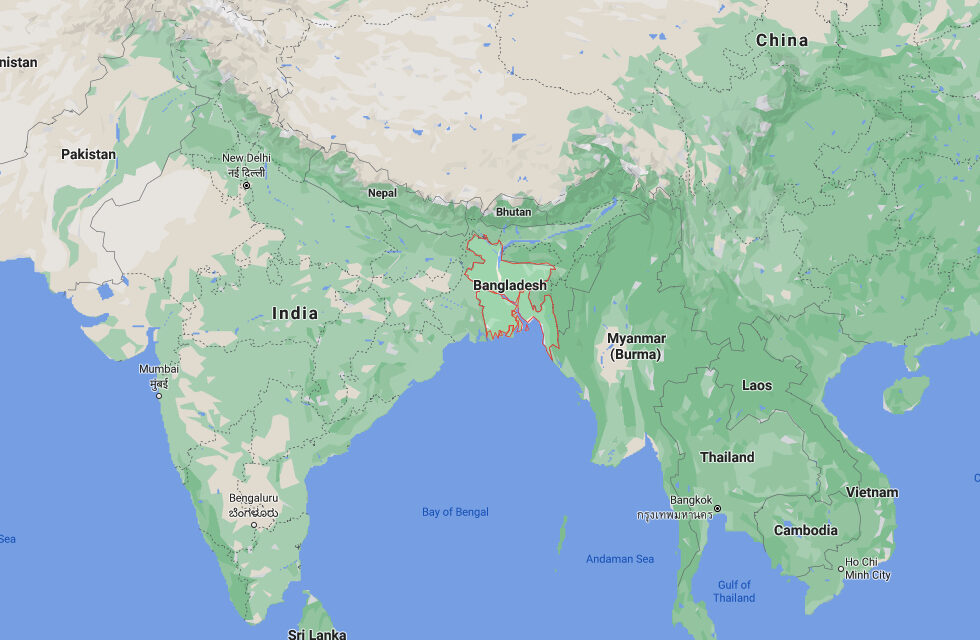

Scientific research using interdisciplinary methods is a fast-growing approach that integrates natural and social science into the pursuit of knowledge. A great example of this method is the work of Dr. Kimberly G. Rogers. She has combined the use of geological sciences and environmental anthropology to uncover new knowledge about the ever-changing delta region of Bangladesh. This knowledge has brought to light new ideas about the interactions between humans and their natural environment.

Dr. Rogers started her journey focusing on natural sciences including geology, and marine & atmospheric science. Her Ph.D. was focused on nearshore and coastal sediment transport, ultimately leading her to work in Bangladesh researching sediment dynamics and land-sea boundaries.

While in Bangladesh, Dr. Rogers got to know the communities in which she worked through her interactions with the people, leading her to develop meaningful relationships with them. She felt these communities were an important factor in the geomorphological processes and environmental occurrences she was studying. Roger’s realization led her to pursue training in Environmental Anthropology at Indiana University through an NSF Science, Engineering and Education for Sustainability Fellowship, ultimately, bringing her into the world of interdisciplinary science.

Fifteen Years and Counting

It all started with the question, “What happens to the billion tons of sediment that come out of the Himalayan Mountains during the monsoon flood every year?” This straightforward, geological question, brought Rogers and her Ph.D. advisor to Bangladesh fifteen years ago.

“Because Bangladesh is on a river delta, like the Mississippi delta, this sediment load is important for building up the landscape, especially when we think about the delta’s vulnerability to sea-level rise…” Rogers said.

As Rogers began to pave her way, there were who contested the existence of sea-level rise and other environmental changes. “Back when I was a graduate student, people in the United States were still talking about climate change being a hoax.”, she reflected. Yet, the people of Bangladesh who lived in the villages with no electricity, nor access to television were expressing they had no doubt climate change was happening. Rogers attributed this knowledge to the fact that many of these people were rural farmers, meaning they worked daily with the land and were experiencing changes on a local level.

In conjunction with this, the country is densely populated. On average, there are one thousand people per square kilometer, therefore, people play a very important role in the physical dynamics shaping Bangladesh. Rogers realized people were not only impacted

by the phenomena that she was studying as a geologist, but they were also perhaps contributing to it.

After receiving the training needed to understand human behavior and decision making, Rogers returned to Bangladesh and began to interview people and collect household surveys. She took the knowledge she gained in informal settings and formalized it through the methods she learned.

“I’m able to talk to people and get the narratives, get their stories, and have that give our data context,” Rogers stated concerning the important connection between her geological and anthropological work.

One Resilient Basket Case

The interdisciplinary nature of Rogers’ work has shed light on some of the flaws in long-held beliefs concerning Bangladesh. The country has been pinpointed as ground zero of climate change for many years. In fact, in 1974, American politician and diplomat Henry Kissinger dubbed Bangladesh a “basket case”.

Rogers said, “Bangladesh is often put out there as a poster child for global change and global warming. It’s a hotspot for vulnerability… that’s basically how it’s been conceptualized by the west.”

One of the early claims that went along with this was that sea level is rising, thus Bangladesh is going to fill up and flood like a bathtub. The models at the time suggested the country was doomed. However, Rogers’ dissertation research suggested otherwise.

The sediment flowing down the rivers and deposited on the delta influenced the rate at which the ground level rose. In order for Bangladesh to flood due to sea-level rise, the rate of ground level change would have to be less than the rate at which the ocean was rising.

Rogers’ research showed that there were parts of the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta, in which Bangladesh is located, where sedimentation rates were actually keeping pace with sea-level rise, thus she was able to show that the amount of sediment coming down from the mountains combined with coastal processes left the delta in a fairly good position.

The issue is, in reality, much more spatially complex. The land surface is moving up in some places and down in others. This begs the question of how sea-level rise will affect Bangladesh in the realm of spatial dynamics. As Rogers points out, there are local scale variations that science must be aware of in order to find answers and solutions.

As important as these findings are to reexamining the narratives surrounding climate change and Bangladesh, there is still much more to the story.

One of Rogers’ main arguments against the view of Bangladesh as a doomed place is the people. She said, “They are a very resilient people and they know how to work with the dynamics that shape the landscape.”

On average, over thirty percent of Bangladesh floods every year due to the monsoons. The people who live in these areas are used to these kinds of events and have learned to live in a place where they are common. Therefore, their experiences are important in determining how to proceed with mitigation and problem-solving efforts. Rogers, and many others, saw this when it was determined that infrastructure plays a large role in creating coastal vulnerability. The discovery was made through studying feedback in physical processes related to the existence of polders- huge coastal embankments meant to protect the delta from flooding- in Bangladesh.

As Rogers talked to people in areas with polders, she found many of them held mixed attitudes toward the infrastructure. “They perceive environmental change through their interactions with this infrastructure system,” Rogers commented. The locals believed the presence of polders were causing many of the issues they were experiencing.

However, people in areas without polders seemed to desperately want them; and the lack of infrastructure in other areas of the delta led the people to believe that their struggles were directly linked to the absence of polders.

The conversations with various people in different communities highlight the fact, as Rogers put it, that we do not live in a one size fits all world; yet, many problems are approached this way. The same solution is used for a problem no matter where and how that problem is occurring; however, Rogers acknowledges that implementing unique responses to each individual problem in each individual place is unrealistic. Instead, she suggests, “We have to find a middle ground that is sensitive to local variations in physical processes and local scale variations in the way people make decisions and work in that space.”

The Impacts of Being Interdisciplinary

![People have called the Ganges-Brahmaputra Delta home for generations. Even in this everchanging landscape people have found a way to build shelter, grow food, and live out life. Just as the movements of the rivers, sediment, and sea effect the way people live, the people have effects on these natural processes. Such connections are the basis of Dr. Rogers' work. [Photo: Dr. Kimberly Rogers]](https://www.coastalstudiesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/cache/2020/09/Rogers-4/1021053670.png)

Rogers’ work highlights why interdisciplinary science is important. For so long Bangladesh was viewed as a place that was wholly vulnerable to environmental change. Through geology, a natural science, Rogers has shown that this viewpoint is not accurate. Still, the people of Bangladesh are facing struggles of large proportions. Leaving them with the idea that sea-level rise will not completely overtake their land is not enough. By implementing social science approaches in order to study the effects of infrastructure on people’s vulnerability, scientists like Rogers are able to conduct research that can help provide people with ideas of how to better protect and maintain their homes, way of life, and livelihoods.

In summarizing why both social and natural science are an integral part of research, Rogers stated, “My science has hopefully contributed something to the conversation that moves us towards solutions that are feasible and much more sustainable; and in the process, highlights the variations in the systems in which we work so that we can contribute creative solutions to problems that are place-based and locally specific.”While Dr. Rogers has many more research projects planned in Bangladesh, her work has already uncovered many important things. By approaching science in a way that takes advantage of different science methodologies, Dr. Rogers has opened doors to improve life, not only in Bangladesh but in coastal communities all over the world.

![The polders that have been installed throughout Bangladesh have resulted in many mixed emotions. While those without polders express a desire for such protection, those with them believe they would be better off without.[Photo: Dr. Kimberly Rogers]](https://www.coastalstudiesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/cache/2020/09/Rogers3/1976151236.jpeg)

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.