Sam Farquhar began her Ph.D. journey amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. At the time, she had recently completed her master’s program in Marine and Environmental Affairs at the University of Washington in Seattle, followed by a nine-month fellowship in Madagascar. There, she worked with others to establish a marine protected area to foster sustainable fisheries and benefit the local community. She was job hunting when the pandemic hit and had little luck finding a place to begin her career.

As fate would have it, Farquhar noticed an advertisement for ECU’s Integrated Coastal Sciences (ICS) Ph.D. program in May 2020. She applied and was accepted into the program under the mentorship of Dr. Nadine Heck, joining the newest cohort of students just three months later in August. She initially hoped her dissertation would expand upon ideas from her time in Madagascar. However, since traveling so far was especially difficult during the first year of the pandemic, she decided to pivot her focus. Instead, Farquhar drew inspiration from her even earlier work. While at the University of Washington, she received a scholarship for Canadian Studies, which ultimately led her to Arctic Canada as the focal point of her Ph.D. research.

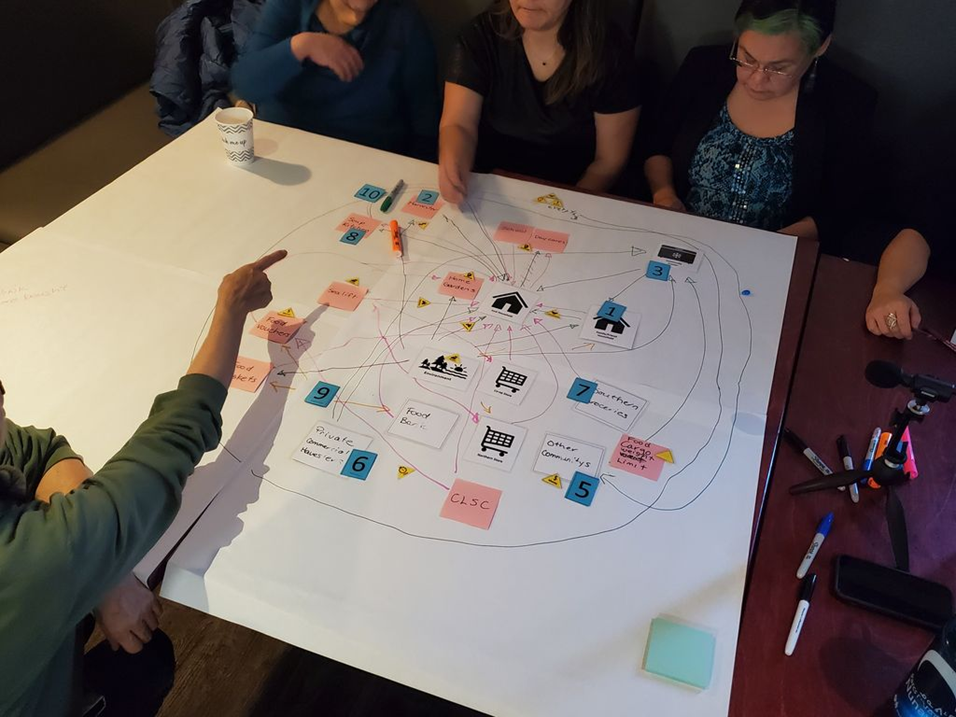

This photo from one of the community workshops Farquhar hosted shows how the participants identified places from which they sourced food and then ranked them by importance and preference.

Specifically, Farquhar wanted to better understand the fishing industry and food security in the community of Nunavik by examining 1) how industrial fishing affects the ecosystem and 2) the social and economic factors influencing access to food.

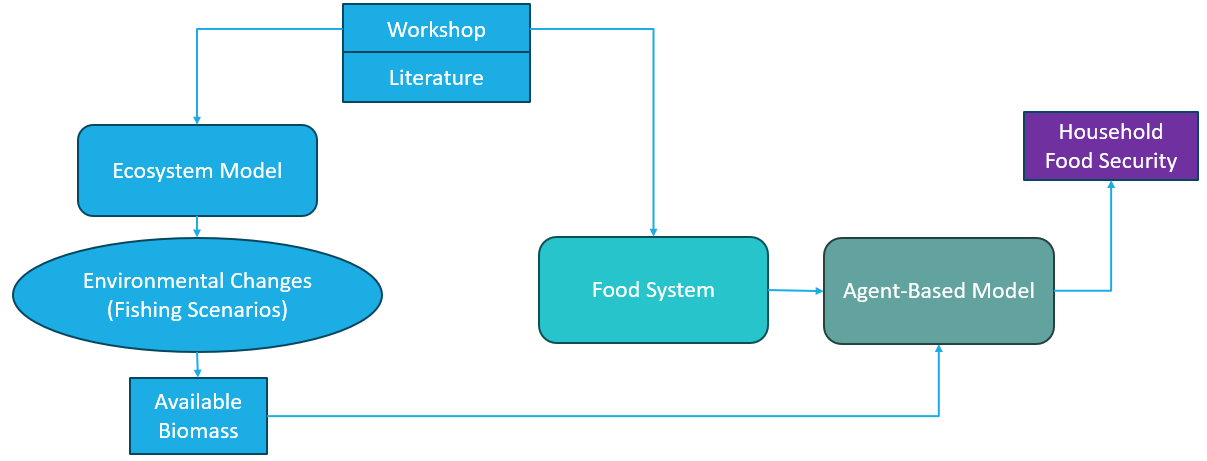

“I’m trying to combine a food system with an ecosystem and link the two together to understand what might happen to food security at the household level. For example, what if we changed the biomass, or species abundance, available for consumption,” Farquhar explains.

To tackle this large undertaking, Farquhar is developing a system of models informed by the practices, knowledge, and opinions of Nunavik’s indigenous people- the Inuit-, as well as current population estimates of predator and prey species inhabiting Nunavik’s surrounding ecosystems.

She collected this information by hosting community workshops and asking questions like “Where are all the places your household secures food from?”. Their typical answers included places such as the grocery store or community freezer, where hunters can leave excess meat they have harvested. Many families also said they secured food from their own harvests, while others also mentioned their household food sources included places such as soup kitchens, school and day care centers, and even places in neighboring communities.

“This [initial research and data visualization] showed that even though I was working in a really small, remote community, it still has a very complex food system,” she says.

Once workshop participants identified the places from which they secure food, Farquhar presented scenarios for them to rank these sources by importance and preference.

“Imagine you are in a household that has low income, and you don’t have a hunter in your family. What is the first place you get food from? The second? The third? Etc.”

Farquhar used this kind of questioning to lay out different scenarios and reveal insights into their decision-making processes. After all workshops had concluded, she took the information she had gleaned and began to make a computer model. The different food sources, preferences, and scenarios gave the model “rules” to follow and make predictions.

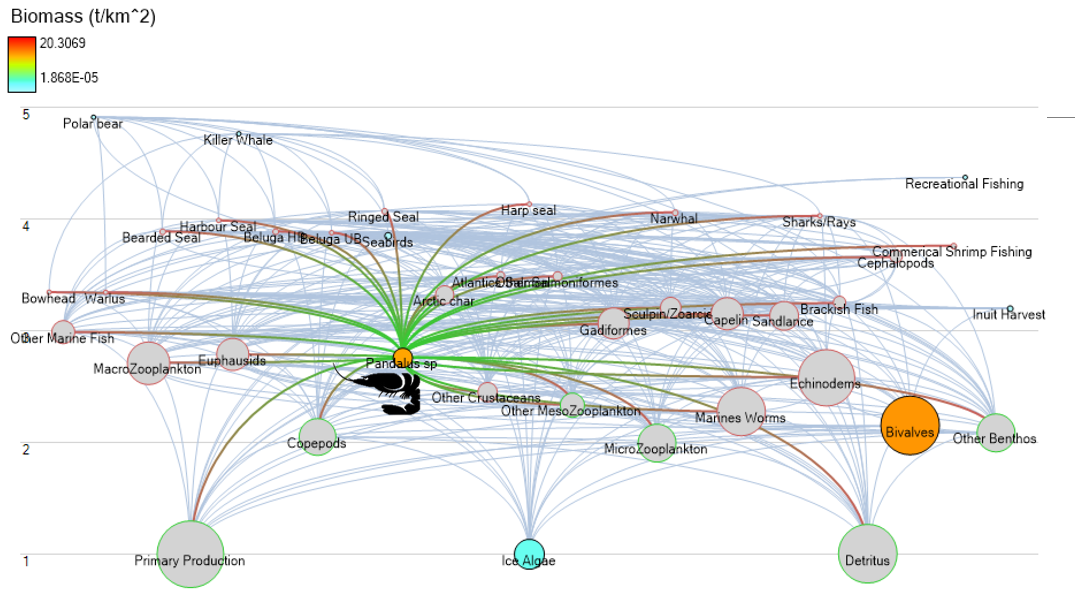

While the resulting model was informative on its own, Farquhar wanted to evaluate the other side of the food system which dealt less with people and their behaviors, and more with the provisions of the ecosystem itself. She collected data from colleagues and previous studies about the local species, as well as what those species produced and consumed, to better understand the area’s natural food web and how the local Inuit population fits into it. By incorporating this ecological data into the model, Farquhar could analyze how changes in animal availability impacted Inuit food sources.

To test her newly updated model, she simulated an extreme scenario where the nearby commercial shrimping industry increased its output by five times.

“[The model] shows us how things will change. In this scenario, the biomass of shrimp decreases significantly, along with other species like salmon and -ones I wasn’t necessarily expecting- narwal and seals. The model reveals both direct and indirect effects on biomass in response to different scenarios. Therefore, if we know there is going to be less of something available for Inuit people to harvest, we can integrate that into the model and future decision-making,” explains Farquhar.

A screen grab from Farqhuar’s computer illustrates the complex food web in Nunavik. The highlighted red and green lines show the predator-prey dynamics of shrimp species in the area.

Although the topic can be daunting and complex, Farquhar has enjoyed her work and is happy with the results thus far.

“It’s been cool because I get to do both social science methods- talking to people and gathering information- and then integrating it into an ecological model,” she shares.

While her full analysis is not quite complete, Farquhar notes that her newly developed models suggest biomass availability may matter less than some social factors, such as food access, when it comes to food security in Nunavik.

As she reflects on her time in the Integrated Coastal Sciences Ph.D. program, Farquhar appreciates the challenges and growth that have come from the integrative part of the program.

“The program has made me elastic in the way I think and piece things together. It’s made me comfortable with being uncomfortable and become more creative, even though it took a bit of adapting at first.”

Farquhar will defend her dissertation in late Spring 2025 . In the meantime, she’s already secured an exciting lineup of opportunities. Early in 2025 the newly formed Center for Arctic Study and Policy at the US Coast Guard Academy sent her to represent the US Coast Guard at a conference in Norway. Farquhar serves in the Coast Guard Reserves and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Additionally, as a recipient of a full Department of Defense scholarship, she will work as a research and development scientist in Washington, D.C., for two years post-graduation.

The preceding story first appeared in the Spring 2025 edition of CoastLines published in May. The work featured in this article was made possible through a Fulbright Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad (DDRA) grant and collaboration from the Universite Laval. It also would not have been possible without the support and knowledge of community members from Nunavik.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.