The students of the UNC Institute for the Environment’s Outer Banks Field Site (OBXFS), hosted by the Coastal Studies Institute, completed their final tasks of the 2023 Fall semester in mid-December. The last of their assignments was to conclude work on their Capstone project, write a final report, and present their findings to the local community.

From their arrival to the Outer Banks in late August to their departure in December, the 2023 cohort spent much of their time here dedicated to studying the presence of artificial light at night (ALAN) in the local community; its possible effects on marine life; and people’s perception of ALAN in the surrounding environment.

Artificial light at night, sometimes referred to as light pollution, is the alteration in the natural levels of darkness at night by the addition of light from human-made sources. Top ALAN contributors include street, car, and interior and exterior building lights. Smaller items such as cell phones and computers can also increase ALAN levels. Previous research has shown that ALAN has both positive and negative impacts. Most obvious to the average observer, ALAN causes skyglow which limits people’s ability to see a clear, starry night sky in all its glory. While sources such as cars and streetlights have real and perceived safety benefits, increased exposure to ALAN can also cause adverse physiological impacts on humans and other organisms. Adverse impacts may include interference with orientation and reproduction cycles, as well as disruption of timing cues for seasonal events, all of which could lead to further behavioral changes in animals. Whether or not the negatives outweigh the positives might be up to individuals to decide for themselves; however, it must be noted that management of ALAN partially depends on public willingness to employ mitigation efforts- those that would reduce ALAN- including, but not limited to, turning off lights after a certain time or using bulbs that emit lower luminance levels.

“I think that turning people’s attention to this topic might allow us to recognize how our patterns or behaviors are being reflected in this parameter- how our use of artificial light at night can be harmful not just to wildlife but to human wellbeing, as well,” said Dr. Lindsay Dubbs, Director of the Outer Banks Field Site.

After pouring over past research studies about ALAN, the students discovered that few had taken place in coastal environments. Thus, their Capstone study design began, and they sought to explore light pollution on the Outer Banks including changes in ALAN extent and levels; its relationship to sea turtle nesting; and the resident and visitor perspectives of it.

A student raises a Sky Quality Meter (SQM) into the air to obtain a luminance measurement at one of their study sites. Photo: UNC Research

Since the students only had about three months to tackle such a complex project, they set some limits on their study. The study area spanned from Corolla to Oregon Inlet, and they only examined data collected from the last decade. The students obtained satellite data to quantify ALAN measurements in the years 2014-2022. They also took ALAN measurements from the ground using a Sky Quality Meter (SQM)- a simple hand-held monitor- once a month during their semester. Additionally, the students were presented with sea turtle nesting data from 2014-2022 by the Network of Endangered Species (NEST) and the National Park Service (NPS), the two entities that monitor sea turtle activity on the Outer Banks. Finally, they distributed a survey in hopes of gathering public opinions about ALAN in the area. With so much anticipated data to examine, the students included five questions relevant to both natural and social sciences in their Capstone research, and they split up into two groups to divide and conquer the work.

From the Natural Science Team

“Our main findings for natural science is that the Outer Banks is losing darkness along the coast, and this is concerning because we know that an increase in ALAN has many different ecological impacts,” says Hessini-Arandel. “We don’t know exactly why we’re seeing these trends, but we know that future research could probably answer these questions.”– Kenza Hessini-Arandel, OBXFS student and junior Environmental Studies major.

How has ALAN changed, spatially and temporally, throughout the Outer Banks over the last 9 years (2014-2022)?

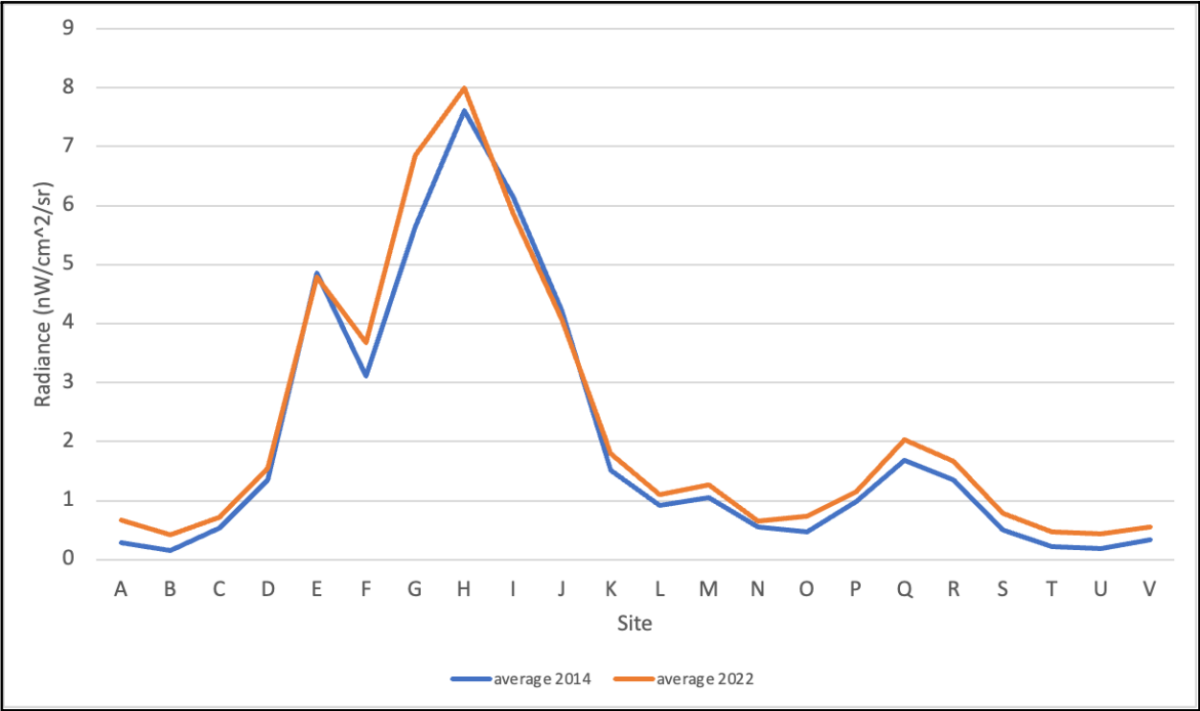

Using satellite data collected from 2014-2022 that recorded measures of nighttime radiance, the students examined changes in ALAN from Corolla to Oregon Inlet. Overall, they found that ALAN increased at most study sites between 2014 and 2022. Though ALAN measurements seemed to be relatively consistent throughout the calendar year, they did see a peak in ALAN during the summer months, likely due to tourism.

The areas with the highest levels of ALAN were the towns of Nags Head, Kill Devil Hills, and Kitty Hawk. Areas that experienced the least amount of ALAN were Corolla, which has less development, and the study areas that fell within the boundaries of the undeveloped Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

Capstone Report Figure 8 shows average levels of radiance in 2014 (blue) and 2022 (orange) at study sites along the Outer Banks. The figure is organized left to right from the southernmost area (A) to the northernmost area (V). Greater radiance measurements were recorded in both years at sites E-J, between Nags Head and Kitty Hawk.

Do satellite measurements of ALAN align with ground measurements?

The students used a simple, hand-held device known as a Sky Quality Meter (SQM) to take on-the-ground measurements in Fall 2023. They visited fourteen beach accesses between Corolla and Oregon during the new moon phases of September- November. They found that the measurements they collected were similar to the average satellite data measurements from the same months in 2022. This is an important finding because the use of the SQMs is an easier and more cost-effective option for measuring nighttime radiance, thus opening doors for local policy makers and other interested individuals to conduct studies of their own.

Is there a relationship between sea turtle nesting and ALAN on the Outer Banks over the last 9 years?

The students found that overall sea turtle nesting activity had increased from 2014-2022; however, contrary to their initial expectations, they did not see a significant correlation between nesting activity and the presence of ALAN. The students offered a few hypotheses as to why this might be.

- Female turtles may not be impacted by the light as they nest.

- There may be a certain threshold of light that must be perceived by the turtles to deter them, and that said threshold has not been met on the Outer Banks.

- Influence of latitude may be greater than any other influence on the turtles nesting in this area since the Outer Banks is nearing the northern range of sea turtle habitat.

- Sample size of the study range may be too small to show any trends.

From the Social Science Team

“We found that there are a lot of people who are willing to support reducing ALAN on a municipal level, but what was interesting was that those light sources that people found more necessary are typically the ones that they found less disruptive, which contributed to some of our bigger findings.”- Drew Huffman, OBXFS student and senior Biology major.

What are the local (resident and visitor) attitudes and views of ALAN on the Outer Banks?

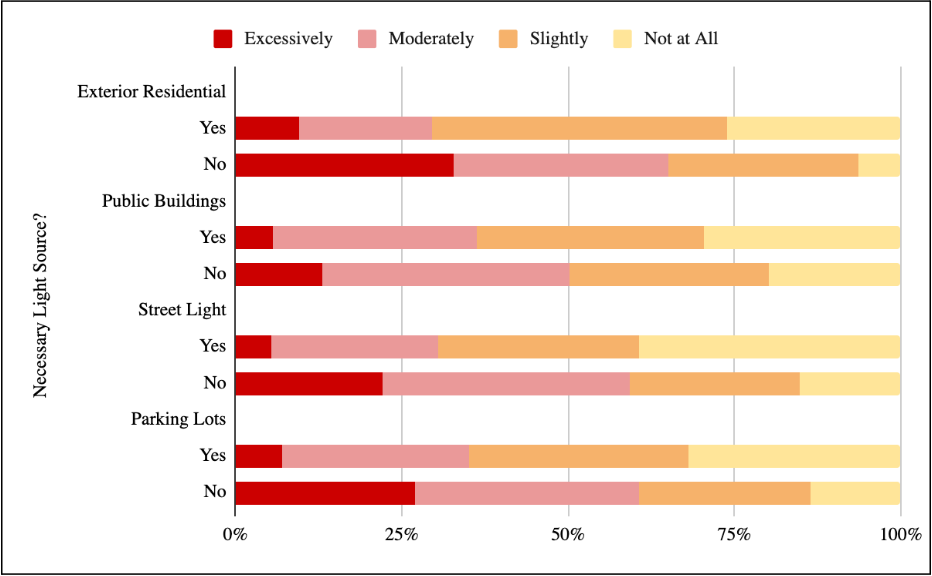

Based on results from their survey, the students found that, overall, individuals can identify light pollution and sources, but are less knowledgeable about the impacts of ALAN. About 70% of the respondents did indicate they had some level of concern about the presence of ALAN. Finally, the survey data suggested that light considered less necessary by the public was deemed more disruptive.

Capstone Report Figure 29 highlights the perceived necessity of various light sources and the level of disruption each causes.

Is there support among residents and visitors for reducing ALAN on the Outer Banks?

Almost 90% of the survey respondents, including residents and visitors alike, agreed to some extent that ALAN should be reduced on the Outer Banks and that they would support individual, commercial, and commercial lighting practices that would do so.

The students provided a few scenarios which could reduce ALAN on the Outer Banks including:

- Establishment of a curfew at which time non-necessary residential, commercial, and/ or municipal lights should be turned off.

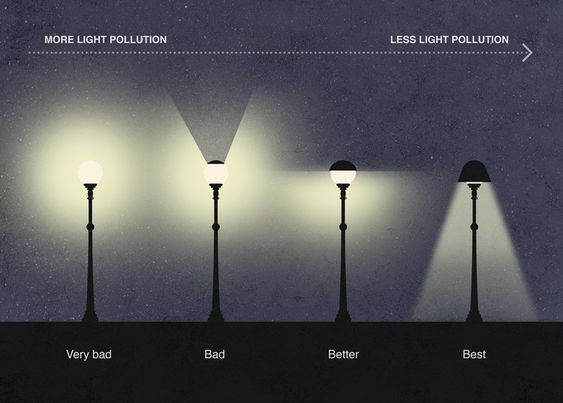

- Requirement that outdoor lights be fully shielded to project light only toward the ground for all new and future buildings.

- Placement of educational materials, such as pamphlets, about ALAN be placed in all short-term rentals.

- Establishment of lumen output limits for all new and future construction.

Light shielding can be provided in varying degrees as depicted above. The students suggest a shield such as that shown to the far right. Graphic: Valeria Montjoy, ArchDaily

Bringing It all Together

After a full semester of not only Capstone research but classes and internships too, the students presented their findings to the local community during CSI’s December installment of Science on the Sound. In addition to the results mentioned above, the students highlighted nuances in the nesting data and demographic trends related to survey responses. While they had very limited time to conduct their work, they outlined several ways in which their study could lead to future work on individual and community levels. They suggested educational campaigns so that people could learn more about ALAN and make efforts to reduce their own outputs. They also mentioned the possibilities of expanding future study efforts to Hatteras Island and other coastal communities, including other marine and coastal animals, and expanding the temporal span of analyzed data. In closing, it seemed that the big take-away was that the more knowledge gained, the better that ALAN and its impacts on all species can be mitigated.

Students huddle together to record their findings at a study site near Jennette’s Pier. Photo: UNC Research

To learn more about the 2023 Outer Banks Field Site (OBXFS) Capstone research project, read the students’ full report, Artificial Light at Night: Public Perception, Sea Turtle Nesting, and Spatio-temporal Change in North Carolina’s Outer Banks, and watch the videos below!

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information.

Based at the Coastal Studies Institute (CSI), the North Carolina Renewable Ocean Energy Program (NCROEP) advances inter-disciplinary marine energy solutions across UNC System partner colleges of engineering at NC State University, UNC Charlotte, and NC A&T University. Click on the links below for more information. ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety.

ECU's Integrated Coastal Programs (ECU ICP) is a leader in coastal and marine research, education, and engagement. ECU ICP includes the Coastal Studies Institute, ECU's Department of Coastal Studies, and ECU Diving and Water Safety. The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.

The ECU Outer Banks campus is home to the Coastal Studies Institute.